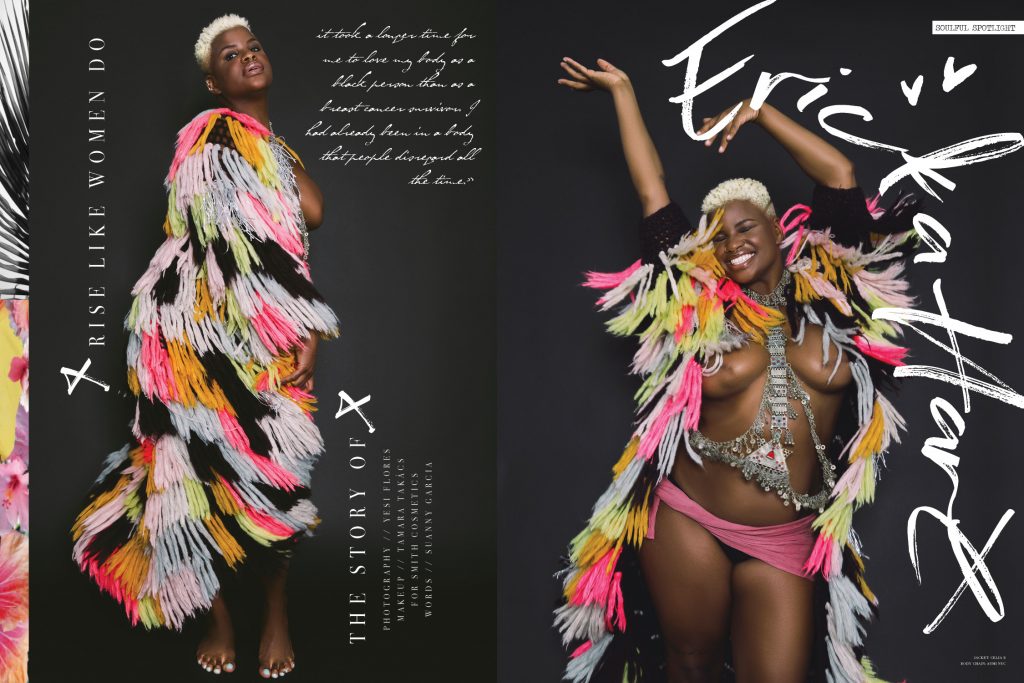

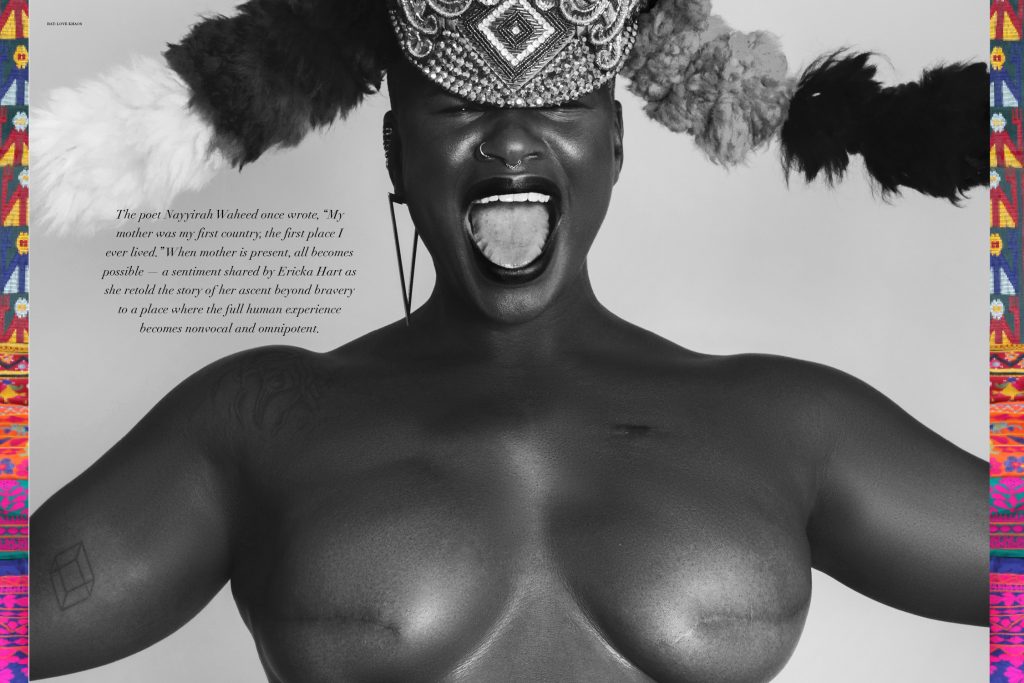

The poet Nayyirah Waheed once wrote, “My mother was my first country, the first place I ever lived.” When mother is present, all becomes possible — a sentiment shared by Ericka Hart as she retold the story of her ascent beyond bravery to a place where the full human experience becomes nonvocal and omnipotent.

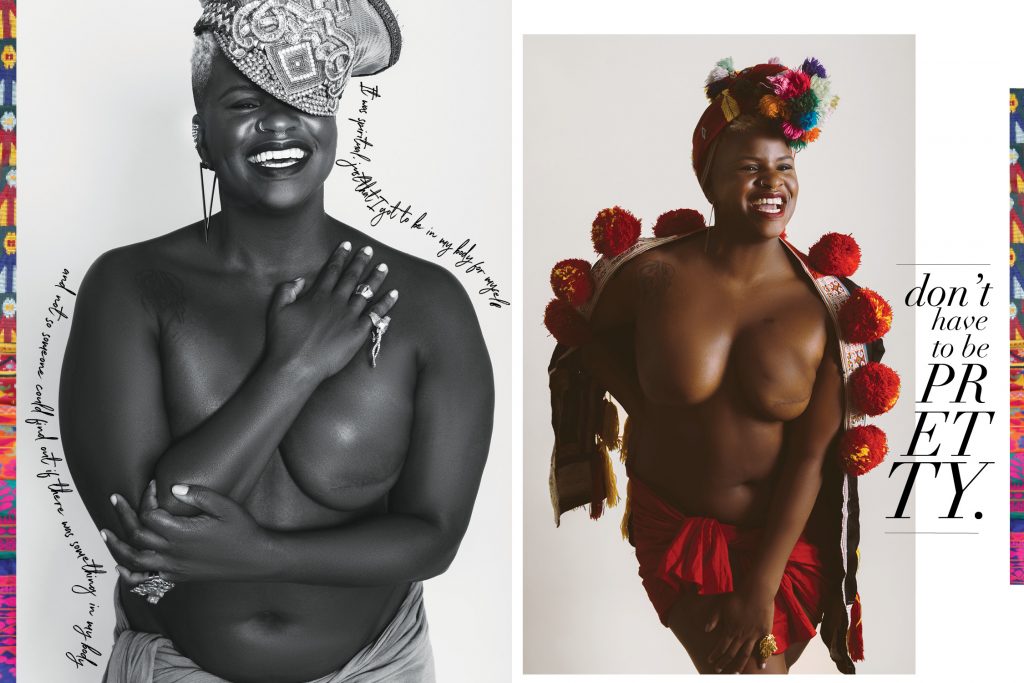

For her, this place was Afropunk 2016 where, after struggling with her own internal dialogue on whether or not to show the world what double mastectomy scars look like on black skin, she chose to take her top off. Her decision rightfully attracted the praise of many, most of which have shared their admiration with Hart. As she wrote in her Afropunk Op-Ed, this noble deed, which she has mentioned was done with the intention to motivate others to check their breasts regardless of age, challenges the notion “that ‘female-bodied’ people can’t take their shirt off due to some androcentric, understated rule that it should not happen in public.” Hart’s reveal allowed her to reclaim her sexuality — to show off her breast in a different context that wasn’t within the frame of a hospital building.

“You spend a lot of time in medical garb and lots of bandages, and to be out in public in a cute outfit topless and not being examined by a doctor is fantastic. I just get to be out here and you get to see me not for some medical purpose. It was spiritual, just that I got to be in my body for myself and not so someone could find out if there was something in my body that shouldn’t be there… yes, I took my top off but it was bigger than that,” she recounts in the car while on our way to the studio.

Hart is one of those rare humans who are fully present and fully open to sharing their stories — a person with a distinct purpose, a soul holding remnants of purity yet harboring a strength that has been exercised persistently. Although others charge her as being inspirational and courageous, she attributes most of her compelling work to her mother’s presence even after death. “My mom passed when I was 13 and I think that she really comes through me. Sometimes I don’t recognize the pictures that are posted. I’m just like ‘I did that?’ I really think she’s here to be like ‘this is my stage right now, I didn’t get to tell this story,” she shares.

Hart has taught sexuality for the past six years, serving everyone from elementary aged youth to adults, and served as Peace Corps HIV/AIDs volunteer in Ethiopia from 2008-2010. One would think it’s only natural to expand on the conversation of how her breast cancer influenced her own relationship with her body. Her response, although not entirely shocking, stirs an important dialogue on blackness. “The common conversation is that when your body changes due to breast cancer, that there’s going to be a shift in how you react to your body, but I didn’t. I didn’t think ‘oh I don’t like my body,’ I was just so happy that I had cleavage, and more importantly, that I was here,” she explains. “People think if you have breast cancer you must hate your body. No, I love my body and I’m also sexy and queer, and super black… it took a longer time for me to love my body as a black person than as a breast cancer survivor. I had already been in a body that people disregard all the time.”

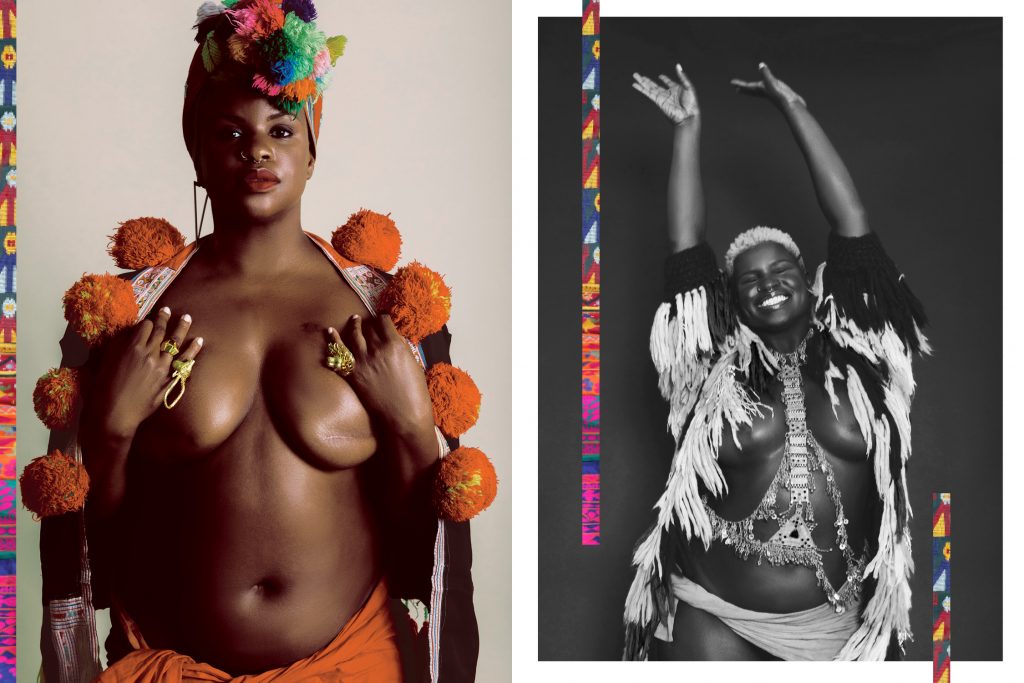

The body is a powerful tool for impacting change, a tool which Hart uses strategically to influence communities, specifically those that are marginalized. She is quite literally the embodiment of the intersection of race, gender, chronic illness, and sexuality. More importantly, her work aims to transcend systems of oppression including those that relate to beauty, those that seek to eradicate the nuance out of beauty, and those that seek to do away with multi-dimensional, cross-cultural and racial expressions of being beautiful. “I talk about dismantling systems a lot so I just got really interested in ‘where does it come from that I am so interested in being pretty?’ I was consumed by that and I realized I’m learning this in magazines, I’m learning this in the media… so I just started understanding that and I was like screw that,” she explains. “I think when you get interested in the system that says you’re supposed to be a particular way and you push up against it, there’s freedom in that because I don’t have to be pretty, I could be ugly, too, which people have called me my entire life, but there’s freedom in just reconciling. Why did we deem ugly as a bad thing? Why can’t ugly just be? And why can’t pretty just be?”

By now, you’re probably as shocked as the entire Disfunkshion staff was after hearing Hart say she has been called ugly her entire life. She explained that although positive feedback abounds, she does receive negative comments mostly pertaining to respectability and nudity. “I’m used to being the person that doesn’t look like anybody else so it was a familiar place. [Nudity becomes] activism for me to the point where I say, I HAVE to do this because I need you to see this also happens to us,” she explains.

It’s no secret that Hart is only just beginning to shake up the world, showing us what unapologetic looks like, educating us on intersectionality and reminding us that breast cancer survivors are just as sexy, stylish and alive as the rest of us. “It’s not just about survivorship or being strong, it’s also that we’re stylish and we’re cute and we have whole lives… I’m also queer. I want you to see all of that,” she contends.

Get free, get nuanced and non-binary is what she continued to express throughout her shoot. After wrapping up, we were lucky enough to spend some time with Hart and her partner, Ebony — who is just as powerful a breath of fresh air and who reminded us all that Hart’s praise is well-earned. We sit down at a local poké shop in Miami — Hart is a fan of seafood — where she enjoyed her first poké bowl, and then walk on over to a local donut shop, where we talk logistics and good ol’ quotidian musings of a day’s hard work. It is through Hart and thereafter that I was reassured of the life-changing power within us all, to alter our own lives as well as others — however large or small that change may be — and to utilize our lived experiences masterfully as they are intended to be used. I found solace in the reminder that the spiritual is found nowhere else if not in each and every one of us, and within the modest, courageous act of being alive.

For preventative measures and for regular screenings make sure you visit your OB-GYN as well as www.breastcancer.org to learn how to conduct an at-home breast exam.

By Suanny Garcia Barales

Editorial Credits:

photography // Yesi Flores

makeup // Tamara Takács

styling // Hugette Montesinos Rodriguez